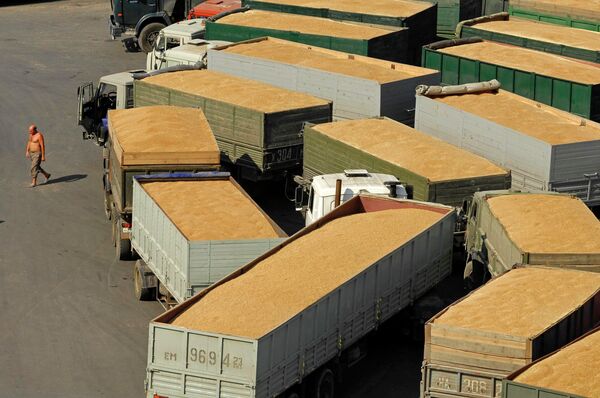

Russia's total wheat exports to non-Commonwealth of Independent States countries amounted to 33.7 million metric tons for the 2017-2018 agricultural year, a 43 percent year-on-year increase, according to a new report. Along with wheat, barley exports nearly doubled, topping 4.8 million tons. Russia also exported 4.5 million tons of maize (a 6 percent year-on-year increase) and 287,000 tons of other crops (a 44 percent increase).

According to Russia's Institute of Agricultural Market Studies, Russia's capacity is far from exhausted and can reach up to 40 million tons of wheat and 52 million tons total agricultural exports in 2018.

Russia first outstripped US wheat exports in 2016 and last year topped total EU exports as well. According to US Department of Agriculture figures, Russia now controls 22 percent of the global wheat market in tonnage, with the EU and US controlling 14 percent and 13 percent, respectively).

According to Maxim Rubchenko, a simple explanation for what caused the boom is that Russia offered a combination of competitive pricing and high quality which the world's top grain importers found attractive.

Also in 2017, France was forced to nearly halve its wheat exports after a drought hit the country, prompting Russia to begin sales to traditional French markets in Africa, including Senegal and Morocco.

Russian wheat is also gaining traction in Nigeria, Bangladesh and Indonesia, and exporters are eyeing Algeria, which plans to lift import restrictions. Last year, Russia even sold 100,000 tons of wheat to Mexico, normally a mainstay for US wheat producers.

Thank the Sanctions

As Rubchenko pointed out, "Nearly all market analysts admit that one of the main reasons for the boom of Russia's agricultural industry has been the sanctions war unleased by the West in 2014. Following the imposition of European and US sanctions, Russia announced retaliatory measures, limiting the import of Western food products. As a result, food imports from the EU fell by 40%, freeing the market for domestic production." In the intervening years, Russian agricultural imports dropped from 35 percent of domestic consumption in 2013 to no more than 20 percent today.

On the export front, a campaign by the government to support producers helped expand Russia's agricultural footprint abroad. The state increased concessional lending and grants, and made corrections to legislation regarding land, allowing for a substantial increase in the sowing area, which exceeded 80 million hectares as of 2017. Subsidized rates for rail transport, the construction of new grain terminals at Russia's ports and the creation of a network of wholesale distribution centers are also expected to help.

"And that's not the limit, not by far," Rubchenko stressed. Russia has at least two other cards up its sleeve, including large amounts of unused farmland.

To this end, the ministry has prepared new draft laws aimed at simplifying procedures for the recovery of these lands, increasing taxes on unused farmland. The government has also increased financing for the agricultural industry, from 242 billion rubles (about $3.85 billion) last year to 272 billion ($4.32 billion) today. Additional funds are expected to be provided for rural development, preferential short-term credit, and the modernization of machinery and equipment.

Diversification

Finally, according to Rubchenko, there's one more factor playing to Russia's favor: climate change. A recent study by Kansas State University noted that compared to the late 1980s, average temperatures in Eurasia's grain-growing regions are set to rise by 1.8 degrees Celsius by 2020 and 3.9 degrees by 2050. Combined with new technologies, these changes will allow Russia to turn an additional 57 million hectares of land into agricultural land.

On May 1, Russia will lift its restrictions on Turkish tomatoes, and Tkachev hopes for a tit-for-tat response from the Turkish side on Russian meat, dairy and fish products. As for China, the minister said that the Chinese side has already agreed to buy Russian processed meat, in the form of canned goods, soups, etc., with negotiations on other products continuing.